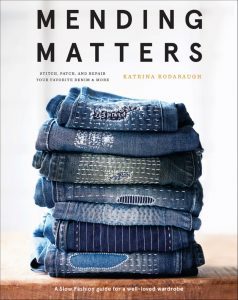

An art project, the Plaza collapse and a pair of jeans that needed mending were all driving forces for award-winning artist and crafter Katrina Rodabaugh to consider her fashion consumption habits. After uncovering the nasty impacts of fashion on the planet, Rodabaugh turned to mending to make her wardrobe last longer. In her new book: Mending Matters: Stitch, Patch, and Repair Your Favorite Denim & More, Rodabaugh explores sewing on two levels – sharing more than 20 hands-on projects that showcase current trends in visible mending, and addressing the way mending leads to a more mindful relationship to fashion and to overall well-being. Enjoy this introduction to Rodabaugh’s journey, excerpted in full from Mending Matters (Abrams, 2018).Get your copy here.

An art project, the Plaza collapse and a pair of jeans that needed mending were all driving forces for award-winning artist and crafter Katrina Rodabaugh to consider her fashion consumption habits. After uncovering the nasty impacts of fashion on the planet, Rodabaugh turned to mending to make her wardrobe last longer. In her new book: Mending Matters: Stitch, Patch, and Repair Your Favorite Denim & More, Rodabaugh explores sewing on two levels – sharing more than 20 hands-on projects that showcase current trends in visible mending, and addressing the way mending leads to a more mindful relationship to fashion and to overall well-being. Enjoy this introduction to Rodabaugh’s journey, excerpted in full from Mending Matters (Abrams, 2018).Get your copy here.

On August 1, 2013, I started an art project, Make Thrift Mend, and vowed not to buy new clothing for an entire year. The project was my attempt as a fiber artist to engage with what’s known as social practice or “art as action.” I used my personal relationship with fashion as the center of my creative experiment. I publicly pledged to make simple garments, purchase secondhand, and mend the clothing I already owned while considering how best to engage with ethical and sustainable fashion. It was akin to a food fast, intended to pause my clothing consumption so I could slow down, reconsider, and realign. Ultimately, this project changed my life, redirected my work, and moved my family three thousand miles to a two hundred-year-old farmhouse to start a homestead. It also positioned me in a Slow Fashion community that continues to fuel me with deeper passion, optimism, and joy than I ever imagined.

Make Thrift Mend grew out of three influences. On April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza garment factory collapsed in Dhaka, Bangladesh, killing more than 1,100 workers and injuring 2,500 more; I heard an NPR interview with Elizabeth Cline, author of Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion; and I read a blog post by Slow Fashion designer Natalie Chanin of Alabama Chanin, in which she advocated for slow design. These three influences converged and created a need for a shift in my own closet. As a longtime environmentalist, I came to the surprising realization that I had left my wardrobe out of my attempts at green living. Somehow, I had overlooked my closet and I wanted a remedy. Soon after, my Make Thrift Mend project was born, and I have abstained from conventional factory fashion ever since.

When I began the Make Thrift Mend project I was living and working in a small apartment in Oakland, California, with my husband and son. I was a regular at our weekly farmers market, tended a backyard garden, supported my local eateries, and prioritized organic produce whenever possible. After having a baby, I also started researching material content in new home goods and prioritized biodegradable products over synthetics. The wool rug was an easy choice over its poly-wool competitor, but I gave little thought to the poly-cotton blouses in my closet. I wasn’t a shopaholic, but I routinely sought new dresses on the sales rack of department stores or cute tunics from my local boutiques mostly based on price, color, and cut. Quite frankly, I hadn’t given much thought to the source of my fibers or their impact on the planet, let alone considered my consumer dollars implicated in a disaster like Rana Plaza. Somehow in the triad of food, clothing, and shelter I overlooked the ecological impact of clothing.

In the first year of my fast I didn’t buy any new clothing at all. I wanted to push “pause” on my fashion consumption. To take this fast one step deeper, I bought only secondhand garments that were biodegradable. Cotton, silk, wool, and linen quickly rose to the top of my list as I bypassed synthetics and took a closer look at garment labels at Goodwill. The more I researched, the more I realized conventional cotton was problematic because of irrigation and pesticides, but I could use natural dyes on secondhand cotton, so I kept it within my parameters. I added this thinking to new fabrics too, although I initially allowed some leeway in notions like plastic zippers, plastic spools for thread, or plastic caps on fabric pencils, as it was nearly impossible to find materials that were entirely biodegradable.

The end of the first year of Make Thrift Mend approached quickly and I knew I had only scratched the surface. This was no longer just a personal art project but an entire shift in clothing consumption and a step toward deeper sustainable living. I recommitted to one more year, although I allowed myself to purchase new clothing if it was locally made or handmade, as I wanted to support indie artisans and handmade goods.

At the end of the second year of Make Thrift Mend I still wasn’t finished. I expanded the parameters on new clothing to include garments from bigger fashion brands that were ethically and ecologically made and ideally organic cotton (mostly because I desperately needed new undergarments, socks, and yoga pants but couldn’t yet make them myself ). I could imagine living within these parameters indefinitely. I wasn’t intent on deprivation so much as mindfulness and realignment, so lifting some of the restrictions felt important as the project kept expanding.

After the third year, I turned my focus to materials. How could I better source my fabrics, threads, notions, and other supplies from sustainable sources? Local sources? Organic fibers? Heirloom quality? This proved particularly challenging, as we had moved from urban Oakland to the rural Hudson Valley of New York and lost access to local fabric shops with inspiring selections of organic cotton, linen, wool, and offerings from independent fabric designers.

Of course, I could travel two hours south to New York City fabric shops, but by that time I had a six-month-old and a four-year-old, so these day trips were rare. I slowed down on making new garments while I reassessed which new homemade ones I really needed, wanted, and would wear the most. Every time I encountered a new complication, I found an opportunity to deepen my connection with fashion, clarify my priorities, and better articulate my personal aesthetic. I like to wear linen and I like to dye linen with plant dyes, so I began researching sustainable linen and organic cotton sources online if I couldn’t source the yardage locally or secondhand. Of course, this meant wrestling with the environmental complications of shipping and packaging, but at each point in sustainable living we have to make decisions, realize there is no perfect solution (just better choices), and do the very best we can.

When I launched Make Thrift Mend I also embarked on a research quest. I wanted to read everything concerning sustainable fashion and find any artist, organization, or website that could help me better understand my options. I read books. I scoured the Internet. I attended events. I took classes. I taught classes. I taught more classes, and eventually I created my own techniques for mending clothing. I studied mending across cultures and recognized the similarities in a basic running stitch to sew Sashiko stitching and Boro garments in Japan, to Kantha quilting in India, to American quilting in the United States, to various styles of darning found on antique linen in Europe. I became passionate about natural dyes and indigo. I offered free tutorials on my website. I hosted mending circles with friends and artists. I even organized public events with other textile artists to highlight Slow Fashion techniques such as weaving, dyeing, stitching, printing, and mending in surprising public settings such as the bustling financial district of San Francisco during lunchtime.

But most important, in that first year of my fast, I fell in love with mending. Most of us typically think of mending as a chore—something to minimize, streamline, or avoid so we can focus on more urgent, essential, or enjoyable tasks. Yet mending transformed into an art form as I realized the opportunity to consider patches and stitches as design elements. My background as a fiber artist helped me find a liberating balance in mending that allowed my stitches to be functional and fashionable. I realized I could approach mending with the same design considerations I used in my artwork—line, shape, scale, texture, color—and I could fuse embroidery and basic stitching with garment repairs to make something that was strangely beautiful and satisfyingly eco-friendly, and proclaimed the garments well-worn but still well-loved.

I realized I could elevate the experience of mending from mundane to expressive. When I stumbled upon Tom of Holland’s Visible Mending Programme, I fell in love with his high-contrast mending on hand-knit sweaters. The inherent subversion of untraceable repairs in Tom’s work was another step in my personal liberation and inspiration, as I found permission to highlight the wear and tear through beautiful stitches instead of hiding the life of the garment. Combine this with the influences of Sashiko stitching, Kantha quilting, American quilting, and European darning, and I was hooked.

Mending came from necessity as I tore the knees in no fewer than three pairs of jeans in the first year of Make Thrift Mend. I’m not sure I would have realized how quickly my jeans were wearing out if I hadn’t sworn off fast fashion—I would probably have replaced them before they tore completely. I discovered several clever ways to mend, but fell in love with the patchwork, running stitches, and indigo color palette of traditional Japanese Boro. This spurred additional research on rejuvenating garments across continents through mending and natural dyes. I taught my first mending workshop in downtown San Francisco and it quickly led to another, and now dozens of workshops and thousands of students later it has become the cornerstone of my work. I didn’t intentionally shift my studio practice to teach mending and Slow Fashion, but now I can’t imagine it any other way.

Through my workshops I have also had the opportunity to work with thousands of students and witness how their garments were tearing, fraying, ripping, and otherwise wearing out. I was able to see how my own mending needed improving; how one solution didn’t fit all repairs, fabrics, garments, or aesthetics; and how students wanted to locate like-minded community at the center of Slow Fashion as much as they wanted to learn mending. It also taught me that our clothes naturally age. Garments consist of fibers, and these fibers weaken with the repeated wear and friction of our bodies. This process is completely acceptable and even expected. We can embrace mending as part of the life cycle of clothing and we can even celebrate it with thoughtful repairs.